The Imponderable Questions at Christmas

Is "Die Hard" a Christmas Movie?

In 1988, an action-adventure novel was adapted for the big screen. Die Hard was released with minor expectations. Hollywood just hoped it would net a modest profit before it would be forgotten.

Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone both turned down the lead role as John McClane, probably because they agree with the Hollywood experts. Sure, people might see the movie, but nobody is going to care about it. It will soon be forgotten.

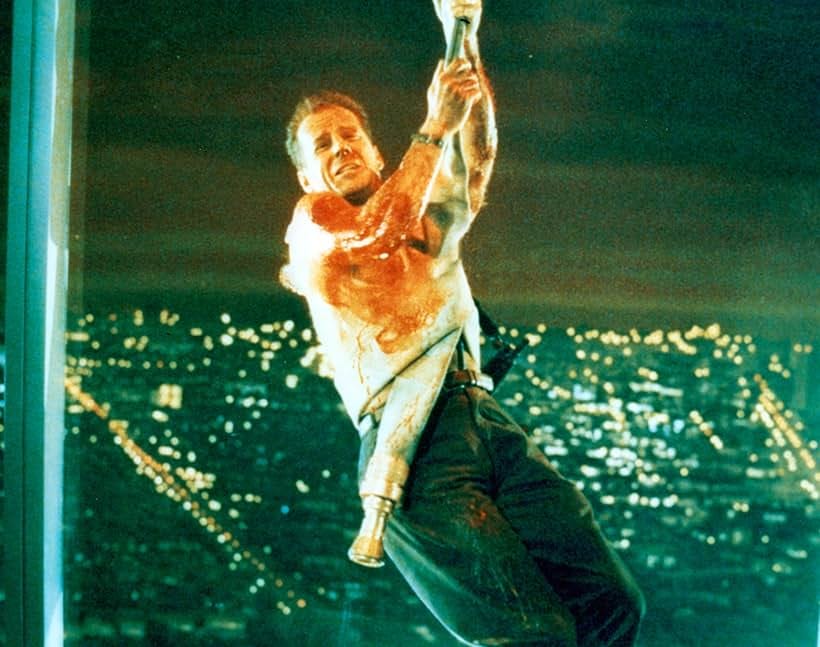

Die Hard became not only a surprise blockbuster hit financially, it became one of the metrics for the classic action-adventure genre. This is a movie where the bad guys speak a foreign language (German, in this case, a homage to the Bader-Meinhof Gang of West Germany of the 1970s), villains cut phone lines, everybody has a machine gun, there are plastic explosives and crazy chases down elevator shafts, fist fights, broken glass, and guys being thrown off roofs. It has some funny one-liners, too.

And the lead character is played by Bruce Willis who spends most of the movie in his undershirt. Movie trivia experts say the costume department for the film had 17 undershirts for Willis “in various stages of degradation.”

This movie that nobody thought much of turned out to be the main of a five-film franchise all revolving around a film character who became iconic: John McClane.

The holidays are a time for family and merriment and celebration, but this time of year is also a time when people ask a lot of difficult questions.

The holiday debate still rages: Is Die Hard a Christmas movie? For some reason this discussion matters to Americans, so Ricochet Cafe is going to weigh in. In our view, there are three things that you need for a movie to be considered a Christmas movie.

The movie must take place at or around Christmas

There must be some Christmas seasonal trappings in the movie

The film has to have a theme that theologically harmonizes with Christmas, the day when Christians celebrate the birth of the Savior.

1. The movie must take place around Christmas

Die Hard checks this box. The movie opens on Christmas Eve when a Japanese real estate developer is hosting a lavish party for his senior staff on the 30th story of his landmark building. The businessman admits he does not celebrate Christmas, but he wants to reward his business executives on this day with a fancy party. This is a complete misunderstanding of Christmas. Most companies give their employees the day off not just on Christmas but often the day before. Even Scrooge-like bosses will allow employees a half-day off on Christmas Eve if at all possible. But this Japanese executive thinks he’s doing his senior staff a favor by not only making them work on Christmas Eve but by keeping them late. So this Japanese executive has some Scrooge-like elements to his character. Nice Chistmas-y touch.

2. There must be some Christmas seasonal trappings

Again, Die Hard meets the challenge. The party that opens the movie is clearly a Christmas celebration, if an odd one. The Bruce Willis character carries an oversized teddy bear as a Christmas gift on the plane. We see decorations and Christmas lights. You can’t watch this movie and think it’s any other time of year besides Christmas.

3. The movie must resonate theologically with Christmas themes

A lot of what goes on in Die Hard is pretty hardcore action-adventure stuff. In a quaint throwback to earlier times, the bad guys in this film are Europeans who smoke filterless cigarettes rather than Middle Eastern terrorists. Some of the cyber breaches that facilitate their crimes are done mechanically by smashing computer terminals rather than via hacking. But all in all, it’s a shoot-em-up movie and that seems quite out of sync with the “peace on earth, good will toward men” theme of Christmas.

However, the world is full of evil, which is the very reason that Jesus came to earth. He came to redeem us from the sin of the world. The sin of the world is on bold display in this film. Just a few of the sins include lying, theft, violence, brutality, and murder. While this makes up most of the movie—and it’s the reason the movie is so memorable—that’s not the theological message. We live in a broken world—everyone knows that.

Die Hard has two main plot lines. On one level, you have the in-your-face action adventure. But on the other level, this is a story about a confused by very tough man, John McClane, who is traveling from New York to Los Angeles to meet with his estranged wife and their children for Christmas.

John McClane is a tough, experienced New York City cop. Besides being built like a mixed martial arts hero, he has mad skills with firearms, keen powers of observation, and great integrity. His beautiful young wife was recently hired to be a big shot at a Japanese company, but had to move to Los Angeles to take the job. There she found money, power, prestige, everything her worldly heart could ever desire. She took their kids with her. Her marriage to John did not break up in the normal way—in fact it may not have broken up at all. They just lived apart and started to pursue different interests. John didn’t want to give up his job in New York and his wife was not about to turn down a power position with the Japanese company in Los Angeles.

He wanted one thing, she wanted another thing, and while she seemed prepared to sacrifice their marriage on the altar of her own desires, her husband is more ambivalent. He’s almost confused about what has happened. He wants to get back together, but he has no idea how to make that happen.

At the end of this movie, they are reconciled. It is not clear how this reconciliation works out in the long run—this is Hollywood, after all—but it is clear that they find their way back to each other.

Reconciliation is a Christmas theme. It’s what the Herald Angels sang when we harkened in the carol— “God and sinners reconciled.” Reconciliation means that a dysfunctional, disrupted, or otherwise broken relationship is restored. It occurs not when one person forgives another (although that is part of it), it occurs when the two estranged people come back together to restore what was lost. To rebuild what was broken. To recover what they threw away.

Reconciliation requires a lot of things: repentance, regret, forgiveness, kindness, mercy, and compassion. It takes understanding and patience. It takes a lot of generosity of spirit. Most of all, reconciliation requires a lot of love.

Jesus came to earth as a baby who grew up to be both fully God and fully man. He is the Messiah, the one who saves us. His death on the cross paid the sin debt that humans owed to divine justice. The result was that God and Christians could have a right relationship once again. They could be restored to what always should have been, but what humans so recklessly threw away.

By His death, Jesus made it possible for God to extend grace and mercy to those who put their faith in Christ. It’s why the Apostle Paul once wrote that he only ever really preached one thing: “Jesus Christ and Him crucified.” That was the event that reconciled a fallen world to a perfect and holy God.

Now in Die Hard this theme is only subtly and imperfectly hinted at. John McClane and his wife Holly are no theologians. There is no Bible in this film, no angels visiting the earth. No one mentions substituionary atonement. The theme of reconciliation is shown “through a glass darkly,” as Paul also wrote. This means we see the contours of it, not all of the divine details.

We see one example of a broken relationship that gets restored only after a whole lot of pain.

John McClane is a man, not a divine figure, and he doesn’t die to satisfy divine justice, instead he lives to defeat the bad guys and ultimately to save his wife. He is quite prepared to do whatever it takes to save her. And his wife—who recently had even stopped using her married name in business—now sees this fallen, violent, wicked world through new eyes. She comes to appreciate her husband’s strength and sacrifices in the face of danger.

The theme of reconciliation in Die Hard works for me to make it a Christmas movie. It’s not a theological film, but then neither is It’s a Wonderful Life. But it does bring a new angle on an old Christmas theme—reconciliation. Reconciliation happens on Christmas between God and humans but it also happens all of the time between humans.

There is one other person who is reconciled in the film. Early in the film, a hapless police officer is asked to investigate some potential nefarious activity at the building the terrorists have seized. This overweight and emotionally defeated officer has more or less given up on life and on his career. He dutifully obeys orders but his heart is no longer in his job.

A bad event had happened earlier in his career as a police officer when he was responsible for an unavoidable shooting death. It was both unavoidable and yet he was responsible, because he pulled the trigger. We only see the contours of this event, which is barely described but has affected this man’s total life trajectory. After that brutal death, this hapless police officer went into slacker mode. He comes across as one of those cheerful guys who is really drowning in his own sorrows.

When he first appears and misses all the clues that a crime is literally taking place under his nose, we learn that his wife is expecting a baby. Their very first baby. He has a little bit of hope on the horizon. Something good has happened to him at last. But he’s still smiling as he is drowning in an unfulfilled life.

He enters the film as a buffoon but concludes the film as a hero. Just as the John McClane and his executive wife reconcile, so does the police officer reconcile himself with his own past. He starts out as a schlub. When other officers get to the scene, he is outranked and abused. The other cops mock his idea and bully and abuse him. They insult him and humiliate him. He is verbally battered by those hot-shot officers who take over the scene, when all he is doing is trying to do the right thing.

And that’s the point: he’s right. He may have stumbled onto the crime scene and he may have missed the first clues that terrorists were afoot, but once things start to unfold, he sees things the other higher-ranking cops don’t see, understands thing they don’t understand, and hears things they don’t hear. He persists doggedly despite the abuse that is heaped upon him and, in the end, he is reconciled back to who he really is.

He was always a good cop. He was always a man of integrity, a man with mad skills, a man willing to risk his life in the defense of others. He was always a protector and defender of his community. And in the end, he becomes that in a way that is undeniable. And did I mention, a baby is going to arrive soon at his house? That’s another Christmas theme—new life. The new life of a baby and the new life revived in a man who is already halfway through with his life.

It’s not your traditional Christmas fare. You won’t get Clarence the angel, the thieving green Grinch, or ghosts from the past in A Christmas Carol. There is no sad Christmas tree for Charlie Brown. Instead, it is a loud, rowdy, bullet-riddled movie about how two people got back together. And how a good cop re-discovered his mojo. At Christmas.

Our vote: Die Hard is a Christmas movie. An unusual Christmas movie, true, but a Christmas movie nonetheless. And the fact that this movie was predicted to be a dud but emerged as the metric by which decades of subsequent action-adventure films are judged is another little Christmas miracle. Sometimes the things you underestimate are the things that really matter.

Merry Christmas!