History

Conspiracy theorists know that the drugs Marilyn Monroe took barbiturates plus booze before her tragic death on August 4, 1962 (curiously, the exact first birthday of Barack Obama, if one believes that he was born when he says he was born). There are three relatively plausible theories of how Marilyn met her untimely end at just 36 years of age (curiously, the exact same age Princess Diana was when she died).

The first theory is that she completed suicide. (That’s the new lingo—one no longer “commits” suicide but rather “completes” it). This is plausible because Monroe had a long and well documented history of mental illness and had previously attempted suicide. She was under a psychiatrist’s care five days a week at the time of her death, and the psychiatrist had assigned a live-in assistant to Monroe, a woman named Eunice Murray. Although many biographies call Eunice Murray a “housekeeper,” her actual job was to keep the psychiatrist informed of Monroe’s many mood swings and potentially aberrant or dangerous behaviors. Marilyn knew exactly who Eunice Murray was—it was no secret that her psychiatrist needed a live-in spy because Marilyn’s mental health was so volatile. An argument in favor of the suicide theory is that the day before she died, Marilyn fired Eunice Murray, giving her severance, a few more days of work, and parting on good terms.

Others maintain that Monroe was murdered and barbiturates and alcohol were used as the murder weapons. It was reported she had taken the barbiturates not by mouth, as was usual for her, but as an enema. That is likely the only way a murderer could force her to ingest a fatal dose. Monroe was known to play around with some dangerous characters, including womanizing politicos and mafiosi. Maybe she got on someone’s nerves or found out something she should not have known. Rumor has it that a detailed diary Monroe kept at her home went missing when she was found dead. The FBI had her house wired and knew who she was talking to and cavorting with—maybe she was becoming a liability. Some say she was murdered, some say she took her own life and there is some supporting evidence for both cases.

The last scenario is that her death was accidental. Monroe was a chronic insomniac and took barbiturates not just to help her relax, but to help her sleep. She was what was known at the time as a “pill popper” and what we today might call a “substance abuser.” She also drank, sometimes to excess. The idea that she might have built up such tolerance to barbiturates that she took too many and chased them with booze could have caused an accidental but fatal overdose. Barbiturate overdose was far from rare.

But this isn’t about Marilyn Monroe. It isn’t even about barbiturates. It is about the miracle drug that came along after barbiturates. Barbiturates were suddenly determined to be dangerous (which they were) and habit forming (ditto). So along came the new improved drug. Meet the new drug, largely the same as the old drug.

Benzodiazepines

By the 1950s and 1960s, people were starting to understand that barbiturates were dangerous. Overdoses could be fatal (another victim of barbiturate overdose was the fiery evangelist Aimee Semple MacPherson, another insomniac). They could be addictive, which, at the time, we described as being “habit forming.” Barbiturates were potentially lethal when mixed with alcohol. And they killed Marilyn, no matter which of the three explanatory scenarios for her death (murder, suicide, accident) you choose.

In 1955, a scientist “discovered” or “invented” a drug that came to be known as Librium. Its generic name is chlordiazepoxide and it holds the honor of being the first of what would become many more benzodiazepines. It was heralded as a safe alternative to barbiturates and by 1963 (a year after Marilyn’s death), Big Pharma introduced us to Valium (diazepam), a drug still widely prescribed today. Benzodiazepines or benzos became popular as the safe alternative to barbiturates. More benzo drugs hit the market: there is Xanax (alprazolam), Ativan (lorazepam), and Klonopin (clonazepam) along with some others. They are indicated for the treatment of seizures (a legitimate use but a rare one) but also anxiety and insomnia.

Love them or hate them, benzos are a cash cow. In 2019, there were 92M prescriptions dispensed for benzos in the United States alone. Believe it or not, that’s lower than it was in 2016, but it’s still dangerously high. People mostly get them by prescription, but you can also buy prescription benzos on the street and there are now dangerous new “designer benzos” made of various synthetic poisons, fillers like baby laxative, a dollop of illicit fentanyl, and possibly even containing some benzodiazepines made in a clandestine lab. Street benzos, euphemistically called “designer benzos,” are very dangerous and potentially deadly.

About 30% of Americans filled at least one prescription for pharmacy-grade benzos in the time from 1996 to 2013. Most of these scripts were written for anxiety. A study published in 2019 found that 12.6% of American adults had taken at least one benzodiazepine in the past year. It’s hard to find anyone who hasn’t been at least offered a benzo prescription:

If you need to get one of those MRI scans where you have to lie in a closed tube, you’ll be offered benzos

You get them almost automatically if you get a cancer diagnosis

If you see a psychiatrist for just about anything, you may get handed a benzodiazepine prescription

If you’re a famous person and you need to do something difficult, like attend a funeral of a loved one, likely a doctor somewhere will make sure you have a supply of benzodiazepines to keep you calm

Tell enough doctors you have trouble sleeping, and you’ll get a prescription for a benzodiazepine

These appalling numbers suggest that just about everyone you know is likely taking benzos. Maybe you are, too.

Short-Term

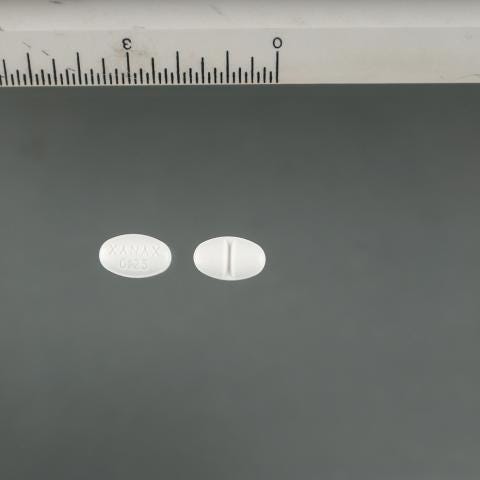

They look harmless, don’t they? Those are a couple of pills marketed under the trade name Xanax. Very lucrative product.

Benzodiazepines have some legitimate uses, such as in the treatment of certain types of epilpesy and seizure disorders and also to help with alcohol withdrawal (detoxification). But most people don’t take them in that context.

The benzodiazepines most Americans take are mainly prescribed for anxiety and related conditions (social anxiety, generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, and so on) but the official advice from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) displayed on the package insert states that they are for short-term use only, typically defined in weeks. (The exception is those who may take benzodiazepines in the context of seizure disorders, who likely need them long term.) However, there is a “high prevalence” of long-term use that can go on for years. Long-term use is so prevalent we don’t even have official statistics, since it’s been medically normalized.

People who are physiologically dependent on benzodiazepines are not drug addicts. Most of the people taking these benzodiazepines are doing so under doctor’s orders with legitimate prescriptions. It’s just that many prescribers think of benzodiazepines as harmless drugs that provide soothing and comfort in times of distress. And many patients do not know the risks.

The ugly side of benzodiazepines emerged almost from the outset, and it is something many physicians and the medical establishment chose to ignore. It’s a kind of medical gaslighting. And maybe it’s not so much doctors gaslighting patients as Big Pharma gaslighting doctors who, in turn, gaslight their patients.

Trickle-down gaslighting.

Withdrawal

Benzodiazepines are not addictive in the classic sense of the term. People don’t take them to get high—once you get habituated to them, you take them to “feel normal.” And people who regularly take benzodiazepines don’t crave them or get high from them. Instead, there is a physiologic dependence that occurs with use, and we don’t even know for sure how long it takes this dependence to occur. For some, it can happen in just weeks. Other people can take benzodiazepines for years and quit them cold turkey without a problem.

For many, stopping benzodiazepines suddenly produces a very unpleasant “acute withdrawal” syndrome that may involve any combination of these problems: abdominal cramps, gastrointestinal problems, anxiety, racing hearts, atrial fibrillation, tinnitus, uncontrollable sweating, trembling, uncontrollable shaking, dizziness, blurry vision, pain in the face or neck, headache, and brain fog. That list is incomplete. The acute withdrawal phase can last days, even a few weeks, but eventually it goes away.

So medical authorities recommend that rather than just stopping benzodiazepines cold turkey, benzo users should taper off the drug gradually. For some people, this works fine. The exact protocol for the taper is somewhat in dispute because it does not seem that one size fits all. Some people taper in four weeks, reducing their dose by 25% each week. This works for some but could result in hospitalization for others. That’s considered a “fast taper” in benzo circles. In reality, some people need years to taper, reducing the dose in very small steps and plateauing at each level. Many people who try to taper off benzodiazepines fail and start back; sometimes people have to try several times to taper off successfully.

With courage, determination, and support, many will succeed at getting off benzos. The weirdest thing of all is that a number of patients will continue to experience often severe withdrawal symptoms even long after they have completely discontinued the drug.

BIND

It’s called benzodiazepine-induced neurologic dysfunction or BIND. The theory is that benzos are neurotoxic and cause brain injuries that persist even after the drug is out of one’s system. For some people, the symptoms of BIND start to occur even while taking the drug. These symptoms include anxiety, lack of coordination, poor sense of balance, headaches (including migraines), bloated abdomen (called “benzo belly”), sleep problems, hallucinations, rapid heart rate, tinnitus, atrial fibrillation, memory loss, poor concentration, fatigue, fearfulness, depression, and even suicidal ideation. Other people experience BIND symptoms during the tapering phase (which can take months or years) and most perplexingly, many BIND sufferers have not taken a benzodiazepine in years and yet still struggle with the symptoms.

The medical challenge with BIND is that these symptoms persist even long after the drug has cleared the body. In fact, there are medical cases on record and published in the peer-reviewed medical literature about cases of BIND symptoms lasting years after the drug has been discontinued.

Heroin users experience withdrawal as their body “misses” its regular infusions of heroin. But once the drug clears the system, the withdrawal ends. With BIND, there is often “acute withdrawal”—as the drug exits the body—but then there is permanent neurological damage. This was observed decades ago and called “protracted withdrawal symptoms” (pronounced PAWS) but no one took it very seriously. Many of the people suffering with BIND suffered in silence; some who came forward to ask doctors and the healthcare system for help were not believed. Some complaining about what we now know as BIND were ridiculed.

BIND symptoms are erratic and unpredictable. People with BIND describe “windows” (periods of feeling reasonably well) and “waves” (when symptoms overwhelm them). For some, a window is less about feeling good than just not feeling so awfully bad.

The problem with BIND, besides the condition itself, is that the medical community is barely aware of this problem. Those that are peripherally aware of BIND may trivialize it or even be skeptical about it. Many BIND people with long-term and potentially life-altering withdrawal symptoms, are not met with dignity and compassion from the medical side. Many doctors even today doubt BIND symptoms or do not understand how these symptoms could possibly be linked to a drug the patient is no longer taking.

It's a little like Long COVID, which makes scientific sense, since there is a real medical condition known as a “postviral syndrome.” (Some viruses have the ability to linger in the body long after the first attack is resolved and attack the patient again, albeit often in a slightly altered form. A good exmaple is chicken pox which can stay in the body for 20 years and re-appear later as shingles. That’s a postviral syndrome.) Yet Long COVID was roundly dismissed by the medical establishment as malingering and mocked by some of the media. The medical establishment declared emphatically that postviral syndrome might exist for some viruses, but certianly not for COVID. That is, until we found out that Long COVID is indeed real. How many patients sought medical care for this condition only to be disbelieved and rejected by healthcare professionals?

It's the same with BIND, only worse. There is very little research into what causes BIND, although neurotoxicity is sometimes mentioned. That is a theory—we have no proof of it other than that its plausibility. There is no consensus as to how to treat BIND, which is understandable since most of the medical establishment does not know it exists. Some have heard of it, but a subset of these people think it’s fake.

BIND is the conspiracy theory of medicine. Some know it exists, others mock them rather than refute the argument. What’s missing is a serious and solutions-focused discussion of BIND.

A proliferation of patient-run support groups has popped up on the internet, providing support, comfort, and lifestyle tips to people with BIND, many of whom are so severely affected that they can no longer work or whose careers have been substantially downsized. People with BIND often experience divorce, family disruption, social isolation, and financial devasation in addition to their other symptoms. Many are lonely and abandoned, left adrift to figure out their medical problems without much help from the people who profit from benzodiazepine sales.

Science Stuff

Is BIND real? A good number of people claim to have it and medical papers and books dating back to the 1980s reported on it. The most notable book on the subject came from Dr. Heather Ashton in the United Kingdom who chronicled those disabled by benzodiazepine use, even long after they had stopped taking the drug. The Ashton Manual, as it is known, is still the most comprehensive and most accessible text on the topic, but she did not use the term BIND.

BIND was coined by more recent researchers, although earlier works talked about protracted withdrawal syndrome (PWS, pronounced PAWS) after benzodiazepine cessation. Some papers were published, describing perplexing “persistent symptoms” long after the benzodiazepines were stopped. In some cases, prolonged symptoms were reported after benzodiazepine use stopped but no further research was conducted.

The main impetus driving BIND research now is due in large part to the fact that people with BIND sought help with this condition and eventually, thanks to technology, found each other online when the medical establishment ignored them.

Today, BIND is recognized by the FDA and there are continuing medical education courses about the nature and reality of BIND. We’ve made a lot of progress, but not enough to stop the disorder. In fact, we do not even really know how to treat the disorder.

Not everyone who takes benzodiazepines will get BIND. The majority of benzo users will not develop BIND, or at least that’s the way it looks based on the limited statistical information available. Some experts say about 30% of benzo users will develop BIND if and when they stop the drug, but that’s a guess.

It is not clear if any one benzodiazepine is more associated with BIND than others, but BIND can occur with any benzodiazepine. And the length of the prescription does not seem to play a role, or, perhaps better said does not play a role in every single case—there are instances of BIND developing in people who took benzodiazepines at low doses for a short time (weeks) and there are people who took higher doses for years who do not get it.

So why do some people get BIND and not others? We don’t know, and it’s an important and intriguing puzzle that demands an answer, because if we could identify the “at-risk patients” our physicians could make better prescribing choices. But for that to happen, they’d have to recognize that BIND exists.

What To Do

This is not medical advice, but there are a few things that even to lay people just seem prudent. Be very judicious about the medications you take. Benzodiazepines are handed out like candy in high-stress environments like oncology clinics and psychiatric wards. Many physicians are quick to prescribe them, but you should be very slow to take them. Nobody ever died from not taking a benzo. (And if you’re unsure as to what is or is not a benzo, the generic drug names of benzos typically end in “pam.” Plus you can just Google the drug name or ask your favorite AI if whatever the doctor is recommending is a benzodiazepine.)

You should never accept a prescription for benzodiazepines (doctors sometimes call them “tranquilizers”) without Informed Consent, meaning the prescriber should be willing to tell you side effects, risks, as well as potential benefits. Some will not even tell you they’re prescribing a benzodiazepine (ask). True Informed Consent means that all of your questions are answered and all of the risks as well as benefits of the drug are clearly disclosed to you in plain language. Any doctor who tells you benzos are safe and can be taken as long as you like has not read the package inserts of benzodiazepines or the “boxed warning” the FDA demanded be put on the product label. For some people, these drugs have heavy consequences that far outweigh their momentary benefits.

Speaking of the FDA, the Agency recommends that benzos be taken for the short term only, so unless there is some unusual medical need or you have a seizure disorder, you should not be taking them for much more than a month. Although benzos are prescribed for insomnia, they are a poor choice for this condition. True, they will work to put you to sleep at first and in the short term, but insomnia tends to be a chronic condition and benzodiazepines are not meant to be taken chronically. And if you’re taking a sleep aid, make sure it’s not a Z-drug, which are benzodiazepine’s ugly cousin. (Ambien or zolpidem is one; the Z-drugs have generic names that start with a Z.) It is a good move to see a sleep specialist before embarking down the path of sleeping pills.

Many healthcare professionals likely assume benzos are safe, because very few people die of them. It’s hard (but possible) to overdose on benzodiazepines. Benzos can accelerate an overdose, like when you take them with opioids since opioids (like oxycodone, morphine, or their street cousin heroin) depress respiration and so do benzos. In fact, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) do not recommend taking prescription opioid pain relievers and prescription benzodiazepines at the same time, because the combination can be deadly. It can cause your respiratory system to slow down to the point that you stop breathing.

By and large, no one dies of taking benzodiazepines and no one is “addicted” in the classic sense. But there is a physiologic dependence that builds up, often alarmingly quickly, that can trigger “acute withdrawal” symptoms when a person stops. But that’s not BIND.

BIND is much worse. BIND may afflict patients with confusing long-term symptoms even after they stop the drug. (BIND symptoms can include brain fog, fatigue, joint pain, gastrointestinal problems, loss of balance, tinnitus, mental health problems, weight gain, migraines, and many more.) BIND has also been linked to suicidal ideation and worse. In many cases, people with BIND develop totally new symptoms after giving up benzodiazepines. For example, it’s not unusual for a person who had never had tinnitus before (or any number of other symptoms) to suddenly develop tinnitus after quitting benzodiazepines.

Benzodiazepines are a central nervous system drug. That means they penetrate the blood-brain barrier and get into the brain. They affect neurons or brain cells. It’s not entirely clear what they do to some of the neurons in the brain, but for some people, the effects can be long lasting. The word “neurotoxicity” is thrown around with benzodiazepines, meaning they appear to damage or poison some of the brain.

Generally, anything “toxic” in the brain is not a good thing.

Do people with BIND ever recover? The short answer is yes, all available evidence to date suggests that most of them do, but it can take a long time. People with BIND seem to do better when they get support, care, and most of all validation from the healthcare system as well as other important people in their life. We don’t have a medical cure for BIND, so those with BIND just have to walk it out. In doing this, they need social support from family and friends as well as care from the healthcare system. BIND can be so debilitating that the people who help their family members or friends with BIND are often known as caregivers.

People didn’t get BIND because they did something wrong or because they took drugs irresponsibly. Most people with BIND today were those who followed doctor’s orders. And while there is such a thing as “street benzos,” most people with BIND got their benzos at CVS or Rite-Aid. With a prescription. Under medical care.

Haven’t heard of BIND? Considering that the benzodiazepine market in 2023 was valued at $3.1B and expected to grow about 4% a year over coming years, it’s no wonder. Benzodiazepines are good business. BIND might be bad for business.

Disclaimer: These opinions are my own. I am not against benzodiazepine use or prescribing, but I do advocate Informed Consent for all drugs but especially for people who are considering benzodiazepines. We need better medical and nursing education about benzodiazepines for prescribers, and greater public awareness of BIND. For some people in certain specific situations, taking benzodiazepines can be a good decision. Benzos do have a purpose and should not be banned. But we need to understand the risks.